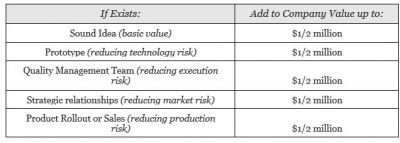

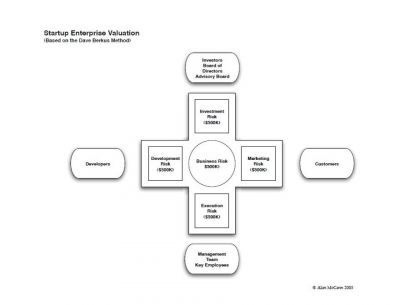

Wednesday, November 16, 2016 Wednesday, November 16, 2016 After 20 Years: Updating the Berkus Method of ValuationBy: Dave Berkus, Dave Berkus, ”Super angel” investor, tech futurist This post originally appeared on Berkonomics.com Well, it had to happen. Originally created in the mid 1990’s to help with the imprecise problem of how to value early stage companies, especially those in technology, I developed what soon became known as “The Berkus Method” when published in the popular book, “Winning Angels” by Harvard’s Amis and Stevenson with my permission in 2001. But a lot of time has passed since then. There is a universal truth: fewer than one in a thousand start-ups meet or exceed their projected revenues in the periods planned. So how do you use financial projections as valuation metrics when you know the odds of those being accurate predictors of the future are so very unreliable? I thought then that the best way to value a start-up is to give value to those elements of progress by the entrepreneur or team that reduce risk of success. It is the exact opposite of giving value to projected financial success, except for the hurdle which I use to filter out smaller opportunities. I must believe that the candidate company, if successful, could achieve some level of gross revenue at the end of the fifth year in business. Today, for me, that hurdle number is $20 million. The Berkus Method assigns a number, a financial valuation, to each of four major elements of risk faced by all young companies – after crediting the entrepreneur some basic value for the quality and potential of the idea itself. Today, the method as explained, adds $500,000 in value for each of the following risk-reduction elements: Note that these numbers are maximums that can be “earned” to form a valuation, allowing for a pre-revenue valuation of up to $2 million (or a post roll-out value of up to $2.5 million), but certainly also allowing the investor to put much lower values into each test, resulting in valuations well below that amount. In 2005, Alan McCann created a graphic representation of the Method: Note that Allan changed the title of the risks from technology-execution-market-production to investment-marketing-execution-development. And he added the cohort responsible for each, a nice touch. I should have done more about this subtle interpretation when first seeing this, and will attempt to make up for that now. Because the Internet has such a long memory and documents from the distant past can be found with ease, a search the “The Berkus Method” today will yield any number of conflicting valuation criteria and element amounts culled from the many subsequent publications of the method over the ensuing years. It has occurred to me lately that the original matrix is too restrictive, and should be a suggestion rather than a rigid form. That is: a user of the Method should be able to list those risks that are most important to the target company and to the investor, and assign maximum values to each that are appropriate to the industry and to the times. For example, $500,000 maximum value to each element yields either a maximum pre-money enterprise valuation of $$2 million or $2.5 million if all elements are “perfect” for a target in the eyes of the investor. Yet, the current HALO Report from the Angel Capital Association containing average pre-money valuations for angel investors demonstrates that the US average, at least for the moment, is higher than this amount. Valuations are higher in Silicon Valley, Silicon Beach, New York and the North Carolina corridor than in Oklahoma City, Kansas City or Miami. The Method should allow for this. The Method should be flexible enough for its users to negotiate or create a maximum valuation they are willing to accept in a perfect situation, and to assign risk elements that might be more important to them than those listed above. For example, in Silicon Valley, a “big data” startup might competitively call for a $1.5 million maximum value per element, while the same startup in Nebraska might find $500,000 appropriate. As for listed elements, a medical device startup might replace “marketing risk” with “FDA approvals risk.” There is no question that start-up valuations must be kept at a low enough amount to allow for the extreme risk taken by the investor and to provide some opportunity for the investment to achieve a ten-times increase in value over its life. Once a company is in revenues, the Method is no longer applicable, as most everyone will use actual revenues to project value over time. The risk is that these options will make a very simple process two steps more complex, frustrating the original purpose of elegant simplicity. But hopefully, the relaxation of restrictions listed here will allow The Berkus Method to live into another generation, survive the effects of inflation, and address better the specific needs of niche market valuations. Tags: |